Insurers’ models not flexible enough to calculate climate risk, BoE warns

Financial policy committee member says 'my takeaway from the CBES is all the major firms have more work that needs to get done'

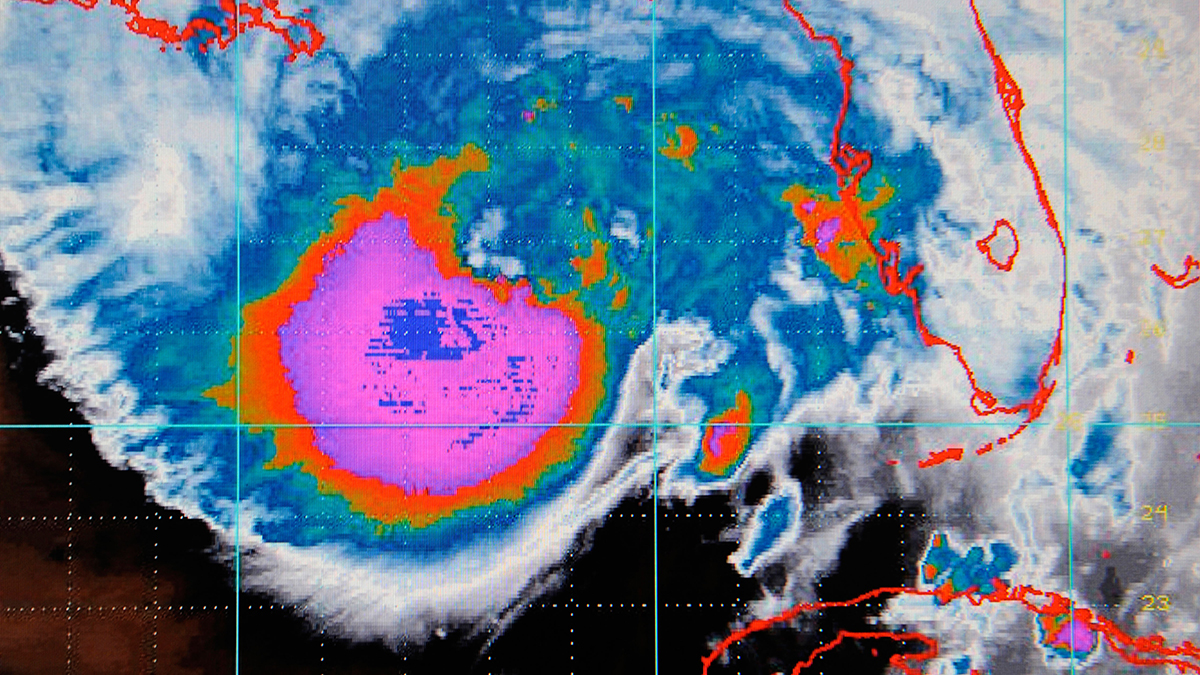

Insurers are failing to consider the risk of flooding and potential losses from perils including storm surge, BoE financial policy committee member Anil Kashyap says

Models used by insurers are not adaptable enough for calculating climate risk, a member of the Bank of England’s (BoE) financial policy committee has warned.

Anil Kashyap, an external member of the committee, said although general insurers had sophisticated models for calculating risk, “many of these models are not sufficiently adaptable to cater for climate-related risks that are expected to increase”.

In a speech hosted by UK Finance, Kashyap said many of the models used by firms often failed to consider the implications of increased water flooding or to assess the impact of potential UK losses from a west coast storm surge. Similarly, only a few insurers were able to estimate the financial implications of different levels of flood defence.

Outlining some of the key findings of the BoE’s 2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES), which was published May this year, Kashyap said even models used by third-party consultants were not flexible enough to accurately gauge climate risk.

In some cases, models used by consultants failed to fully follow their client’s instructions regarding what assumptions were to be made, while in other more complex cases their models oversimplified assumptions in a way that was not always consistent with the scenario provided.

Even within firms, Kashyap said, there was “a lot of variation” in how different parts of the same organisation modelled risk. This, he said, suggested there “are limits on how much having the right tone at the top buys in terms of managing climate risk”, adding: “My takeaway from the CBES is all the major firms have more work that needs to get done.”

Insurers are also failing to collect the necessary data about their clients to properly assess climate risk. For example, the value of property is expected to change if the price of using carbon increases, yet firms rarely know anything about the energy efficiency of their client’s property portfolio.

Similarly, firms rarely know the physical location of their client’s suppliers. As climate change is expected to affect different areas in different ways, this makes it impossible to properly judge the risk of disruption.

“Modelling climate risk will require financial services firms to look at their customers differently from how they do now,” Kashyap said, adding insurers would have to start asking more “non-standard” questions to get the information they needed.